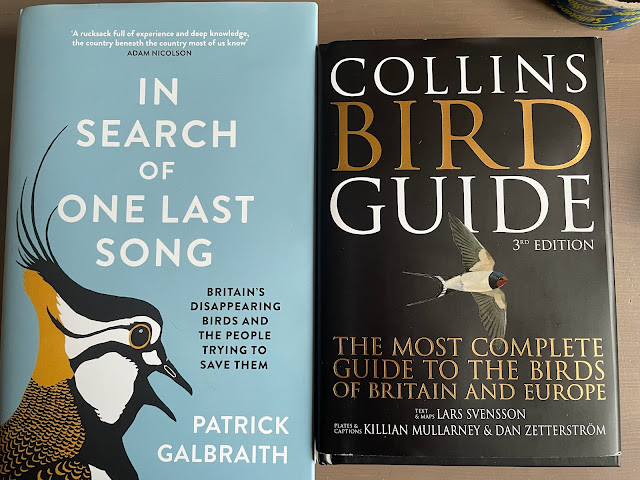

This is one of my very occasional bird book review blogs where I look at two recent additions to my library, namely “In search of one last song- Britain’s disappearing birds and the people trying to save them” by Patrick Galbraith and the recently released 3rd addition of the “Collins bird guide” bible by Sevensson, Mullarney and Zetterstrom.

I’m going to assume that you are familiar with the 2nd edition of the Collins bible, my go to book for identifying UK birds. I don’t suppose there are too many UK birders who don’t own a copy. I find the layout of my well-worn second edition to be spot on with excellent plates, descriptions, and range details. It is 13 years since it was published during which much has changed in the UK avian landscape, almost entirely for the worse and pretty much exclusively driven by man’s seemly insatiable greed and appetite to wreck his own planet.

I opened my Amazon parcel on the day of release of the third edition with great anticipation but, I’m sorry to say, that I was more than a little disappointed. The cover blurb say “ The third edition of this classic brings it completely up to date” but unless the authors are working to either their own or some other species list which I do not recognise, it doesn’t. Take for example the Bean Goose complex. This was split into two separate species, namely the Tundra Bean Goose and the Taiga Bean Goose approximately 5 years ago by the BOU. This is not reflected in the third addition. Another example would be a bird I’m very familiar with from my days birding in Oxfordshire, the Red-crested Pochard. It is stated to be “a regular vagrant to Britain with 10 -50 birds annual, and a few breed. They are definitely resident and breeding in some numbers on the gravel pits of Oxfordshire. On a number of occasions I have counted individual wintering flocks exceeding 50. While this might seem like nit-picking, I worry that if the details of a bird I’m very familiar with are wrong what other mistakes are there?

On a more positive note, the vagrants section has been updated with approximately ten new birds and the descriptions of many of the birds in it are longer and much more through compared to the second edition. Many of the plates in the main section have also been expanded with helpful new images including juveniles and wing details which help with differentiating between similar species, for example Common and Thrush Nightingale. The Warbler plates, however, where much potential for species confusion exists, appear largely unchanged.

It may seem like heresy to criticise the Collins bird bible but my advice is to stick with edition 2 if you have it and save the £30, it’s not worth it!

With the money you have saved I would highly recommend investing in a copy of the fabulous “In search of one last song”. I must confess that I was unaware of the book prior to receiving it as a birthday present from my lovely daughter-in law. If you are familiar with some of the regular nature diaries in many of the UK newspapers, for example the excellent one in the guardian, you will immediately recognise the style of writing. Each chapter is dedicated to one declining species and is narrated through encounters with country folk, their recollections of these once common birds and their attempts to save them.

As an example, the first chapter is dedicated to the Nightingale and its sad demise. I did not know that the introduction of non-native Muntjac has been disastrous for our native common Nightingales. Wherever they are present in any numbers they graze the tangled forest undergrowth down to the ground hence removing the Nightingales breeding habitat. However, all is not doom and gloom and counter measures such as fencing off areas and culling the Muntjac are helping Nightingales recolonise some old locations as some of the author’s encounter’s with folk trying to save the Nightingale show.

I found some of the chapters detailing meetings with those who would generally be consider the enemy by birders, for example gamekeepers, very informative and well balanced.

The chapter called “Putting down roots” dedicated to the fast declining Capercaillie was a difficult and sometimes controversial read. Two birds shot on a hunting trip in 1785, by when they had been long extinct in England, are believed to be the last of the indigenous Scottish Capercaillie . After various failed reintroduction attempts a viable population was finally established in the ancient Scottish pine forests in the mid 1800’s. Officially there are now just 1,200 birds in the remnants of Scotland’s pine forests and there are very few people who don’t believe that their second extinction has almost come. The author describes his visit to the Seafield estate which has the biggest remaining capercaillie population. Ewan Archer has worked here for thirty years as a gamekeeper and he now has responsibility for trying to save the Capercaillie on the estate. Seafield, at over 30,000 acres makes up 9% of the remaining pine forest. Sadly, his view is that there are more like just a few hundred left in total in Scotland and they don’t have much time left. He should know as he spends 6 nights a week out all night monitoring and protecting the leks. RSPB Abernethy is next door which was brought from the Seafield estate as their flagship Capercaillie reserve but Ewan says they are doing very badly there. On Seafield his estimate is that, on average, only 0.2 chicks fledge per nest with the main losses due to predation by foxes, badgers and crows. The rising population of pine martins is also hitting the Capercaillie hard as they take eggs from the nest. Two years ago Springwatch asked if they could film at Seafield but the estate said no. Ewan says that they knew that Seafield has the biggest Lek in the country but their controversial predator control methods would mean that “they would try and get us shut down!” Lots of Food for thought!

Ardent birders will certainly take issue with the views of many of those interviewed in the book but overall I would highly recommend it as a thought provoking and informative Christmas read!

Comments

Post a Comment